I recently had the privilege of seeing one of Mindum’s shoe horns in, as it were, the flesh. It only needed an 900km drive to Melbourne rather than a 17,000km voyage to Blighty, which moved it from the realms of fantasy to something we could do over a couple of days. Despite a few years of studying photographs, I was totally unprepared for the amount of detail and the delicacy of line on the horn. I was able to spend some hours photographing and taking measurements. And possibly drooling just a little. I’d like to think my theories from the earlier post have been confirmed by what I saw, but feel free to call me on confirmation bias if you disagree.

This is going to be a long post, opportunities like this don’t come up every day and the workmanship on the horn deserves a thorough treatment, and to be lavishly illustrated. Endnotes don’t work particularly well in an on-screen format, so I’ve restricted them to references and put most of the information in the link, so hovering over the note number will display the reference without having to follow the link. If you do follow the link, use your browser’s Back button, or click on the number at the start of the note to return to the original point in the text.

Also, be warned: my engineering training is going to take over at some point on this one. If the language seems insanely technical at some points to you non-engineer types out there, that will be why. Third person passive voice is the real give-away, you’ll know it when you see it. I’m using SI units, friends from the USA, Liberia and Myanmar may have to do the conversions to your preferred units yourselves. Where the the measurement is remarkable in customary units, I will point it out. It’s probably not a bad idea to check out the size of the French pouce, you may like to redo the calculations in them.

For the sake of clarity, let’s sort out what arbitrary names I’m calling things before we start.

Top – the widest end of the horn. It would once have been curved but has worn and chipped to an approximately straight edge, with part of the design creating a weak point for the chipping to follow.

Left – the left side when viewed from the front with the design the right way up. There is repaired closed damage and delamination about one third of the way down this edge.

Right – the right side when viewed from the front with the design the right way up.

Front – the part that was the outside of the original horn. This is the decorated surface.

Back – the part that was once on the inside of the whole horn. Undecorated other than the two initials.

Tip – the narrowest part of the shoe horn, originally at or near the tip of the cow horn.

∅ – mathematical symbol for the empty or null set, used to denote circle or hole diameter in engineering.

If you are unfamiliar with the names of the different parts of letterforms that are used in the section on the inscription, there’s a good guide here.

The Shoe horn

Shoe horn, made from the inner curved side of a cow’s horn. Pale for most of the length but darkening at the tip.

Some wear, the curved wide end of the shoe horn has worn away, removing the last 7-9mm of the design and inscription, including the surname of the first donor. A terminal “H” remains. From this and the size of the missing portion matching that occupied by Elsabeath Smith’s surname, the surname of Margreat has been inferred to also be Smith. The length of the extant portion is approximately 200mm.

The tip has been turned back to form a hook to assist in use. There may be damage to the tip, at some point it has been spiral bound in a fine fabric strip 12mm wide. There is some evidence of glue, the fabric/glue has darkened with age. A suspension hole 3.5mm in diameter has been bored approximately 30mm from the tip, there is a semi-circular chip (or wear) on the right side level with the hole, and a diagonally polished line 3mm wide leading from the hole back towards the tip on the left side. This may be evidence of the use of a ribbon or cord for suspension. The hole has the edges rounded on the inside, but the edges on the outside remains unrounded. There is no decoration from the tip to the hole and from the hole for a further 8mm toward the top. The remaining part of the front is covered with decoration.

At some point, something heavy has been placed on the shoe horn, resulting in delamination running into a semi-circular crack leading to the edge on the left side, about 60mm from the top. The other end of the delaminated section has split out along the line of the decoration. A chip 20mm wide and 10mm deep is missing, taking some of the border pattern with it. The chip runs along the mark-up line at the top of “HO” in the word “SHOING”. The delamination has been skilfully repaired with two tinned or silvered 1/8″ (3.17mm) diameter iron rivets. An attempt has been made to align the parts of the decoration but due to internal stresses in the horn, the edges of the crack are now 0.8mm out of line. Curiously, the rivet heads are on the inside of the horn, the peened ends are on the outside. This may be to minimise the area of the decoration covered by the rivet heads or to present the smoothest possible side to the user’s socks. The coating on the rivets is probably tin, as there is a slight yellowish tint to the metal and no evidence of the black sulphide you’d expect to see if they were silvered. The part of the rivets visible from the front are a stable brown iron oxide, with a very fine silver coloured edge from the coating. The rivet nearest the top has been peened to 4.4mm ∅, the other remains at 1/8″ (3.17mm) ∅. From the materials, dimensions and quality of the work, I estimate the repair to be of Victorian period or earlier, and to have been done by a clockmaker, instrument maker or similarly skilled person.

The inside of the horn has been highly polished by use, probably from the woollen socks or stockings of the period. The initials EG have been branded into the back of the horn, reading from tip to top, with the base of the letters near the delaminated section. The letter forms are much more recent than the inscription, and may be the initials of a later owner. Due to the internal curve of the horn, the initials are burnt 1.5 mm more deeply at the base of the letters than at the top. The letter E is 12mm high by 8.3mm wide, the G fits a 12mm x 12mm square area. The brand provides a useful control sample, demonstrating the colouration of this particular horn when burnt, and the shape of the edges and base of an impression left by a hot tool.

The Decoration

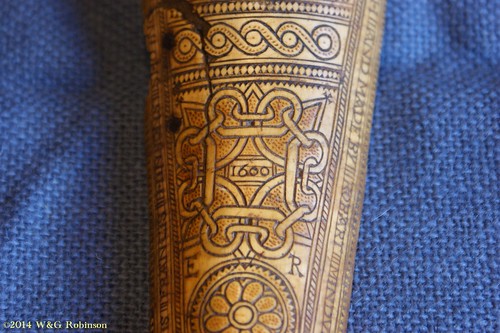

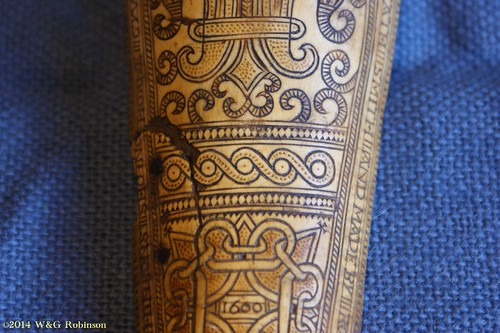

Mindum’s shoe horns are usually divided in to between two and four primary fields separated by a band of knotwork or scrollwork, depending on the size of the horn. Each field may feature one or more design elements. This horn has three primary fields separated by two bands of scrollwork, the top two fields are narrower than the lowest one, and are surrounded by the inscription. The top field contains a fleur-de-lis with arabesques filling the spaces; the second a chain work scroll. The chain surrounds a label displaying the year 1600, the lower middle link supports a medallion bearing a flower. The bottom field is the full width between the outer borders, and contains a series of overlapping arches, looking somewhat like fish or armour scales.

The entire design is outlined with pairs of parallel black lines, 0.8mm apart, the pair near the tip are perpendicular to the long axis of the horn and define the outer limit of the decoration. Both these perpendicular lines meet the outer of the perimeter lines. Around the outside the perimeter pair of lines appear to be parallel to the original edge of the horn. The lines look to have been done at the same time with a single tool, while the depth of the cut varies as you go around the edge of the horn, the pair are both cut to the same depth at any given point. Another pair of parallel lines also 0.8mm apart run approximately 2.5mm inside the first pair, apart from an 8mm long section on the right near the tip, where the separation narrows to 2.0mm. The space between the pairs of lines is filled with pairs of opposed triangles making bow-tie shapes, leaving raised, undarkened diamonds between them. In the centre of each diamond is a small red spot. The bow-tie shapes appear to be in groups of three along the straight edges and the perpendicular space near the tip, any misalignment affects at least three shapes, misshapen diamonds tend to appear at the third diamond in a sequence where he has attempted to correct the alignment. The triangles in the bow-tie are 1mm wide across the base and 1mm high, making each pair 2mm high. Some triangles are incomplete, the base having an unfinished appearance. Variation in width where the triangle is completely present is less than I could measure with my calipers (±0.025mm or ±1/256″ depending on which scale I was reading). In the last 8mm on the right, where the height tapers rapidly from 2.5mm to 2.0mm, there is a clear step in the height and width of the bow-ties. There are five bow-ties 0.8mm wide at the base and 1.6mm high, and appear to be arranged in a group of four plus a single on a slightly different alignment.

Arrows indicate the start and finish of the smaller bow ties

The inscription and the lower of the primary design fields fit within this outer border. The inscription is dealt with in its own section, below. The inscription and another band of border frame the upper two of the primary design fields. Another pair of parallel lines 0.8mm apart is 2.05mm from the centreline of the inscription, a 2.5mm wide band of hatching and another pair of yet parallel lines 0.8mm apart. The hatching is hand done, the spacing and angles are erratic, particularly around the curves where he’s working against the grain. This is where we see Mindum’s ability to repeat and align a pattern — the variation in the spacing can be nearly a millimetre either way. The vast difference between the precision of spacing of the bow-ties and triangles and that of the hatching leads me to think that a different technique was used, and some form of mechanical aid to spacing was used for the former objects.

The top primary design field occupies the top arched area under the inscription and borders. It is 42mm wide at the widest point, 38mm wide along the bottom edge and 46mm high along the long axis of the shoe horn. The field is occupied by a fleur-de-lys[1] which extends to the top and both sides. It is only approximately symmetrical, the outer petal on the left side being marginally larger than the one on the right. The upper part of each outer petal is outlined with a double line 0.6mm apart, a line of stippling 0.6mm away from the line, then another black line also 0.6mm away from the stippling. Inside that is a pair of curved black lines with 1mm hight and 1mm wide triangles along the upper edge. The interior is filled with hatching. The lower edge repeats the pattern and spacing of the upper edge of the petal. The petals end with arabesques, all Mindum’s fleur-de-lys extant from 1597, 1598, 1600, and two in 1604 have the arabesques on the petals. The lower part of the petals extend below the cross-band, the lower edge being two parallel lines, 0.6mm apart with the inner one not quite reaching the tip. The upper edge is a single line, the area between is filled with red stippling. The centre petal has parallel sides for half its height, filled with V shaped hatching, then a collar and opens up in to a diamond, outlined with double lines and with a smaller diamond also outlined in double lines in the middle. Hatching fills the space between the diamonds. The part of the middle petal below the bar is outlined with double lines, and is filled with red stippling. Arabesques come from every point, those at the top and bottom are double and curl in opposite directions. Facing pairs of arabesques fill the remaining space in this frame.

The stippling appears to be done with a needle, knife point or V-shaped gouge, sliding the point into the horn surface and then lifting, leaving a long triangle shape with two cleanly defined long edges and one shorter feathered or torn edge. On this particular horn, all stippling has been filled with red.

The border pattern of two pair of parallel lines 0.8mm apart and 2.0mm high bow-ties is repeated above and below a band of scrollwork 4.0mm high, obviously done with compass and knife. The scroll is about 1mm from the left border, but ends well short of the right one, the inner edge of each curve is 1.6mm radius, and the outer edge is 3.15mm radius, both using the same centre point. There are five circles in this band, the centres are 6.3mm apart, the lines alternate passing under and over each other. There is a line of red stippling running along the middle of the scroll, and the centre points are filled in red. The border pattern of parallel lines and bow ties repeats, completing this band.

The second primary design field is 55mm high, 33mm wide at the top, 22mm wide at the bottom and sits within the inscription and borders. Along the top is a row of downward facing triangles, each 1mm high and wide, symmetrical about the long axis of the horn. It features a chain work design with eight triangular links constraining loops of a continuous scroll, the two upper corner links terminate in crosses made from three triangles, each 1mm wide and 1mm high. The chain surrounds a label displaying the year 1600. The label is 10mm wide and 5.5mm high, outlined with double lines 1mm apart. The corners are clipped by the inner loops of the scroll. A baseline and meanline have been marked to guide positioning of the digits, the lines are centred on the centre of the label. The 1 and 0s are 1.8mm high, the riser of the 6 extends 0.5mm above the meanline. The area within the scroll and triangular links, other than the lower middle triangular link is filled with red stippling. The lower left triangular link (apparently accidentally) extends into the left border. The lower middle triangular link supports a medallion bearing a French heraldic White Marigold. There is no English heraldic equivalent for this device, see the symbolism section below, for discussion.

The initials E R (Elizabeth Regina) appear above and to either side of the medallion, the letters are larger than those in the inscription, approximately 5mm high, but are constructed from the same arrangement of cuts and long triangles. The shape of the medallion gives lie to the claim that the shoe horns were flattened before being decorated rather than being left with a natural curve. The outer circle when measured along the long axis of the horn has a 20.4mm ∅, but when measured across the horn has a diameter of 21.0mm due to the curve moving the surface lightly further away from the compass. When measured on life sized photographs, these diameters are both 20.4mm, so the apparent diameter in two dimensions is consistent. Due to this distortion, I’ll only give dimensions of the medallion along the long axis of the horn as there is no distortion in this direction. The inner part of the flower is drawn with a pair of circles, on 3.0 and 3.6mm ∅. Nine petals span the space between this and a circle with a 12.7mm ∅. The petals are filled with red stippling and have a slight clockwise twist, which may show an attempt at adding some animation to the flower or may be an artefact of the direction of working. This effect is not apparent on any of his other horns with the marigold. There are larger, hand cut triangles between the petals, pointing to the centre of the circle. Each is slightly different size to suit the gap it is in. Outside this is another circle of 15.0mm ∅, then a pair at 18.8 and 20.4mm ∅. Within the 18.8mm circle is a single row of triangles, 1mm wide and 1mm high, with red dots midway between each pair of points. Some of the triangles are misaligned, not being in contact with the circle. These misalignments occur singly.

The base of this section aligns with the start and finish of the inscription and accompanying borders. The transverse parallel border lines and bow-ties again appear, the upper edge is 28mm wide, the lower 27mm. Another scrollwork band occurs here, with the same diameters and spacing as above. The scroll is about 0.4mm from the left edge, has four circles with the last circle ending well short of the right margin. The upper arm of the last scroll is extended across to the right margin, meeting it in the lower right corner. Centres and a line of stippling are in red, yet another border pattern finishes the band.

The lowest primary field is 27mm wide at the top, 20mm wide near the tip, and 24mm high. It is filled with five rows of overlapping curves that look like scales. Each scale is made from three curved lines, the lower two 0.8mm apart and the upper 5.3mm. The arch of the scale is filled with red stippling, the compass point is present, but camouflaged by the stippling.

A final parallel line and bow-tie border lies over the side borders and completes the decoration.

The Inscription

The inscription is in a serifed majuscule hand, with letter forms pre-dating the 1630s. In this early modern form of written English, the letter I can represent either i or j. From around the 1540s in England, V was taken to represent the consonantal u and U the vowel sound, but Mindum seems to use a different convention of using V for both sounds. Could this perhaps show a background of Middle French (1500-1700) where U was used at the start of the word and v elsewhere regardless of sound, rather than English? Renaissance Italian (in transition to modern Italian from 1580 to about 1612) is also a possibility for the same reason, Mindum’s use of W precludes a Middle Polish (1500-1700) or Early New High German (1350-1650) origin. Spelling had not yet been fixed in English this period, but Mindum shows a remarkable degree of consistency with his spelling across the entire opus, again possibly showing a link to French, where spelling had been normalised around 1500. Italian spelling was just beginning to be normalised during this period, the first dictionary being published in 1612. The main spelling variation we see is in people’s names, for example, see the variations on William, which may reflect the owner’s preferred spelling or even accented pronunciation of an Anglicised name.

I’ve interpolated the heights of the letters in millimetres (shown inside brackets) in the inscription at particular points. The pipe character | indicates where Mindum put a vertical line between words, missing parts of the inscription are shown in square brackets.

(2.5)THIS IS ||| FRANCIS ||| HINSONS ||| SHOING HORNE ||| GYVEN BY |||(2.5)MARGREAT [||| SMIT]H AND ||| (3.2)ELSABEATH ||| SMITH ||| AND MADE BY(3.0) ||| ROBART ||| MINDUM(2.3)

We see a similar height expansion over the curve at the top of the horn and compression of the tail of the inscription on the 1612 horn for Mistris Blake, in that case on the last two parts “DOMINI ||| 1612”. It’s possible he adjusted the height in order to reduce the space required rather than change the aspect ratio of the individual letters to squeeze them in. If this is the case, it again hints at someone professionally involved with the proportions of lettering and spaces. I can’t tell from the photos if this is a common element on his other horns.

The letters fit between a capline and baseline done with very fine cuts, the capline is much finer than any of the paired border lines. The letters cross the lines at some points, so the mark-up lines appear to be have been done before the lettering was cut. The imaginary centreline of the lettering is parallel with, and 2.05mm from the inner of the pairs of border lines. Where the letter height varies, the letters heights are symmetrical about the centreline so the space above and below the letter increases evenly.

There are two different size serifs on the inscription. Generally on the letters consisting of straight strokes, the serifs are long, and account in many places for 30% of the letter height. The letter I stems appear to be two facing large serifs, with a medial diamond joining the parts. The letters H are constructed from two pairs of facing serifs as stems with a crossbar, the Ts and As have arms made from a pair of horizontally facing serifs, and are 60% of the letter height. The smaller serifs account for approximately 20% of the letter height, these are used on the stem and stroke of the T, A, and the spurs on curved letters such as C, S and G. Large serifs are the same size throughout the inscription. The Es illustrate the use of both together. The stem is a vertical cut, the base and top are made with the large serif forming the beak and the small taking the place of the serif. The cross-stroke is made from the smaller serif. In places where the letter height is lower, the serifs take up more of the letter height to the point in the word MINDUM where the I appears to have the points overlapping slightly, resulting in a thicker stroke.

The letter cuts are marginally wide at the horn surface than at the base of the cut, resulting in a V shaped profile. The width varies with the curve on some of the curved letters, apparently where Mindum has laid a knife blade over slightly to assist in negotiating the curve. The large and small serifs have absolutely vertical sides and are flat at the bottom. This is consistent with the use of a hot metal tool to hot-stamp or brand the serifs, and the appearance resembles the branded initials on the back. For a description of how knife-cut triangles look, see the part on stippling above.

A Proposed Method

Horn is a thermoplastic material. To get the even, deep, fine cuts evidenced on Mindum’s shoe horns, the horn has to be worked hot. He must have had some readily available heat source, possibly using charcoal from the fire in something like this chafing dish brazier.

Surrey/Hampshire Red Borderware chafing dish, 1550-1699 MoL ID no: 5819

Mindum would have heated the horn before using edged tools to make cuts, there’s a spot on the left, just above the F in Francis where he may have made it hotter than he expected because both the parallel lines at this point cut deeper and are wider than in other places. It isn’t out of the realms of possibility to suggest he also heated metal tools and used these to stamp or brand the horn as part of the decoration. I think I can see two different sized long triangular tools used on the lettering, at least two on the reversed diamonds, and two different sized equilateral triangle tools used hot in the decoration.

The way the misalignment of bow-ties and triangles seems to change at regular, fixed intervals implies Mindum used tools that had multiple elements, I think I can see two tools for the small bow-tie; a single and a group of four, 3.2mm wide. Similarly for the larger bow-tie; a single and a group of three, 3.0mm wide.

I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest there may be no black or brown ink applied to the design on this one, just the branded/burnt edges left as they were made. This also simplifies the problem of not getting black into the red bits.

The Culture and Symbolism

This section is entirely reconstruction based on the evidence of this and some of the other horns. It is an informed guess at best, and may be nothing more than romantic supposition. Do not take my prejudices on the method or the man as subjective truth unless they align with your own research. Be aware the symbolism is open to other alternate, but equally valid interpretations.

From a linguistic study of the names and inscriptions on half a dozen of the then known horns, the editor of the Journal of the British Archaeological Association[2] in 1868 came to the conclusion that Mindum and at least some of his customers may have been of German or Dutch origin living in England. In my previous post on the methods, I concluded that he was likely to be a “stranger” (a foreign worker who is not a guild member). If we extend the editor’s German or Dutch to be Western European Protestants living in England, I think we are on the money. Let’s have a look at the symbolism on this one, and a couple of elements from some of the other shoe horns before looking at the cultural fit.

Fleur-de-Lys — probably best known from the arms of France, the fleur-de-lys is used by many cultures and organisations in their symbology, notably Scotland for the edge of the banner, the English Royal arms, the French flag until 1798, and particular forms associated with Northern France and Holland, and Florence towards the end of the medieval period. Most interesting in this particular case, it was adopted as their sign by the Huguenots in London, now commemorated by Fleur-de-Lis Street (although the street name is of later date than the period in question here).[3] If Mindum were an Huguenot, this neatly meets my requirement of working as a “stranger” and explains the linguistic quirks the editor of JBAA and I have both noted.

White Marigold I had quite a bit of difficulty identifying this symbol because I was initially only looking at the early Modern English design palette. The closest I could get was the heraldic sunflower, more properly, a heliotrope, but the proportions of the diameter of the disk to the length of the petals on all Mindum’s shoe horns exclude it. As a side-path, it lead me to the same symbol being used on many so-called “Sunflower chests” of Huguenot manufacture in the colonies in America. Except it’s not a sunflower there either, it’s a white marigold.[4] It was then a small step to discover that the white marigold was adopted by the Huguenots after the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572, drawn from the French use as a symbol of sorrow.[5]

Scale pattern The lower panel on this horn and a number of others feature a fish-scale or arch design. I don’t have anything for that, I feel I’m tantalisingly close to something, but I’m having to work so hard at it that I’m probably seeing a pattern that isn’t there. I’ve found the same pattern used by a goldsmith working in London in 1720, himself a confirmed Huguenot. Then there’s the same pattern echoed in the terracotta roof tiles of the Calvinist and Lutheran region of Trièves,[6] but those were thatched roofs in Mindum’s time and the tiles only date to the mid nineteenth century. It also doesn’t explain the diamond pattern on his other horns. Sometimes a scale is just a scale.

I’m yet to identify the other common element, the branch or tree. I’m not even sure what it is, I suspect it’s a laurel or olive branch but I haven’t seen any compelling reason for either identification, and both have similar symbolism.

The initials E R that sit either side of the marigold refer to Queen Elizabeth, still reigning when this shoe horn was made. There’s a reference to Elizabeth on just about every one of Mindum’s horns, often initials (at least until Elizabeth’s death in 1603) or the encrowned Tudor rose.

Crowned Tudor Rose It isn’t on this horn, but let’s look at the symbolism and see if it can clarify anything. It must have been important because it is possibly the most common of all devices on Mindum’s opus. Note the crown is a queen’s crown (compare the crowns of the chess queen and king) and continued to be under the reign of King James Stuart (1603-1625). No horn shows a cypher of I R (James Rex) or any reference to the Stuart monarchs.

English Protestants had experienced persecution and execution under the reign of Bloody Mary, so must have empathised with their co-religionists in France. The St Bart’s Day massacre had a galvanizing effect on the parliament, court and Elizabeth. England’s ambassador to the French court, Sir Francis Walsingham barely escaped with his life.[7] Elizabeth was being wooed by Francis, Duke of Anjou, (son of Henry II of France and Catherine de’ Medici) at the time. Following the massacre, Parliament begged her to not marry him, and she sent him away. Waves of refugees arrived in England, Elizabeth taking a personal interest, had bespoke housing built – narrow and tall with well lit upper rooms to enable household industries like silk weaving to bring in income without competing with the existing industries. She encouraged the establishment of French speaking congregations in churches across the country. The Huguenots responded with gratitude, commemorating it by incorporating the Tudor Rose into their art. For example, there is a Tudor Rose encircled within the crown of thorns painted on the under-croft/crypt roof of Canterbury Cathedral, where the a French Protestant congregation still worships. [8]

Tudor Rose and Crown of Thorns in Canterbury Cathedral Undercroft.

Photo by The Rev. Mark R. Collins.

Tudor rose “slipped and crowned” from the Pelican Portrait of Elizabeth I.

Artwork of English origin uses this form of crown.

By the 1590s, there were over 15,000 foreign Protestants in the country, the majority Dutch protestants fleeing Spanish occupation and almost all of the remainder Walloon and Huguenot escaping from France.[9]

The Strangers made some significant changes to Elizabethan life and industry, setting up window glass making on an industrial scale for the first time and revolutionising paper making, printing and bookbinding, and industries dependent on metal: wire making; pin making; copper beating; knife and scissor making; lock making; surgical instrument making; iron and copper cookware manufacture. Many of these people would have the necessary skills, materials and tooling to effect the repair on our horn.

The Name Evidence

Any naming evidence is going to be circumstantial and really prove nothing more than some of the people who are named on the shoe horns have the same surnames as recognised Huguenot surnames. Of course, many businesses selling family crests and shields are built on less evidence than that.

An added complication with is sort of study is that those “…with French names changed them to the English equivalent or modified them after a few generations, thus l’Oiseau became Bird, Le Jeune became Young, Le Fevre became Smith, Le Noir became Black and Le Coque became Cox.” [10]

I’ve done a quick survey to see if anything remarkable popped out from the surnames on extant opus of Mindum shoe horns. I don’t think I’ve really come up with anything constructive, other than Rose Fales (1598) – possibly Anglicised form of de la Fay and the two Smiths (1600), which could be an Anglicised form of Le Fevre [Gwynn – Huguenot Heritage].

Thanks to Alex for humouring and trusting me to not make off with the shoe horn and Gregory House (author of the Red Ned — Reluctant Tudor Detective series of eBooks), for providing the initial pointers to Elizabethan Huguenot symbolism.

A Somewhat Selective Bibliography

BAA, Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume XXIV, p73 (1868)

Fox-Davies, A C, A Complete Guide to Heraldry TC & EC Jack, London 1909. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Complete_Guide_to_Heraldry accessed 27 April 2014

Gwynn, Robin D Huguenot Heritage: The History and Contribution of the Huguenots in Britain Sussex Academic Press, 2001. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=WiqBIA5upsIC&lpg=PA97&ots=oo2w9jYwST&dq=huguenot%20printing&pg=PA106#v=onepage&q&f=false accessed 4 April 2014

Gwynn, R History Today Volume: 35 Issue: 5 1985 — England’s ‘First Refugees’, http://www.historytoday.com/robin-gwynn/englands-first-refugees accessed 24 April 2014

Safford, F G, American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. I, Early Colonial Period: The Seventeenth-Century and William and Mary Styles The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Notes

1 Heraldica, The Fleur-de-lis, http://www.heraldica.org/topics/fdl.htm, accessed 26 April 2014.

2 Journal of the British Archaeological Association Volume XXIV, p73 (1868)

3 Spitalfields Life—The Huguenots of Spitalfields, April 24, 2013 http://spitalfieldslife.com/2013/04/14/the-huguenots-of-spitalfields/ accessed 30 March 2014

4 American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Volume 1, p220, note 6

also A Tradition of Craft: Original, Reproduction, and Adaptation Furniture By Kerri Provost, April 2, 2012 http://www.realhartford.org/2012/04/02/a-tradition-of-craft-original-reproduction-and-adaptation-furniture/ accessed 30 March 2014 and

Philip Zea, Furniture – The Great River: Art & Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635-1820 Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985, p. 187.

5 Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of America, October 10, 1894, to April 13, 1896 Volume III — Part I https://archive.org/stream/proceedingsofhug35hugu/proceedingsofhug35hugu_djvu.txt accessed 2 April 2014

6 Sur les pas des Huguenots—Le Percy–Mens http://www.surlespasdeshuguenots.eu/Sentiersitra2/le-percy—mens.htm?id=10&&Langue=2&HTMLPage=/en/etapes/etapes-francaises.htm accessed 13 April, 2014. See the Heritage tab.

7 Budiansky, S, Her Majesty’s Spymaster: Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the Birth of Modern Espionage, Viking 2005, Chapter 1

8 The Rev. Mark R. Collins Sermons, Seminary Notes, Some Other Stuff… — From the bottom to the top…, 27 July 2007 http://markrobincollins.blogspot.com.au/2007/07/from-bottom-to-top.html accessed 4 April 2014

9 Gwynn, R History Today Volume: 35 Issue: 5 1985 — England’s ‘First Refugees’, http://www.historytoday.com/robin-gwynn/englands-first-refugees accessed 24 April 2014

10 Soutter, C G Huguenots – Rearguard of Westward-moving Israel, http://www.orange-street-church.org/text/huguenot-rearguard.htm on the Orange Street Congregational Church website, accessed 2 April 2014

Really nice work indeed. Its the most sophisticated work ever seen by me.

Hello,

I am just getting this shoe horn to put up for sale and I would like to use some of your description in our text for the web site and newsletter and would be grateful if you could get in contact to confirm if this is okay with you.

Look forward to hearing from you.

Regards,

Richard Gardner

rg@richardgardnerantiques.co.uk

PM sent.

Pingback: Two more shoe horns by Robert Mindum | The Reverend's Big Blog of Leather

Pingback: William bloody Morris’ bloody powderhorn | The Reverend's Big Blog of Leather

Pingback: The Hinson shoehorn is for sale | The Reverend's Big Blog of Leather